As parents or caregivers, we all want to do everything we can to keep our babies healthy, safe, and thriving. One of the ways we do this is by minimizing their risk of developing foodborne illnesses or food poisoning.

These types of infections can cause more severe symptoms in babies because of their weakened immune systems (as compared to adults), which are still developing. Knowing the risks, signs, and how to prevent foodborne illnesses in babies can help you make safe choices and protect your little one’s health.

Table of Contents

What is a foodborne illness?

Foodborne illnesses are infections caused by harmful germs found in contaminated food or water. These germs are too tiny to see with the naked eye, but can easily affect your baby’s health.

These infections can cause various symptoms that range from mild to severe. Adults might be able to fight off these germs without much trouble, but babies’ immune systems are still developing which makes them more vulnerable to infections.

Foodborne illness vs. food poisoning in babies

These terms are often used interchangeably but there are subtle differences between the two.

Foodborne illness is a broad term that refers to any sickness caused by eating or drinking contaminated food or liquids.

This includes infection with harmful germs (like bacteria, viruses, or parasites) or even allergic reactions that you can get from tainted food or drinks (ie. when a food unknowingly contains something that you’re allergic to). Some common examples of infections that you’ve likely heard of are E.coli and Salmonella.

Symptoms can appear several hours to days after consuming the contaminated food, making it harder to pinpoint the exact cause. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and sometimes fever. Depending on the type, it can last from one day to weeks.

Food poisoning is a type of foodborne illness that happens when harmful germs, like bacteria, create toxins that contaminate food, causing various symptoms.

The germ itself doesn’t cause food poisoning, rather the germ produces harmful substances (i.e. toxins) that do (1).

Symptoms of food poisoning such as intense nausea, vomiting, stomach pain or cramps, and sometimes sweating typically appear quickly, even within a few hours. Food poisoning symptoms are usually intense but short-lived, often resolving within 24-48 hours once the toxins are out of the body.

Why are babies more at risk from contaminated food?

Babies are more at risk for foodborne illnesses than older children or adults for several reasons. First, their immune systems are still developing, meaning they have fewer natural defenses against harmful germs (such as bacteria and viruses) that may enter their bodies.

Additionally, their tiny digestive systems aren’t as efficient at breaking down and eliminating pathogens, making it easier for bacteria to take hold and cause infections.

Another factor is their delicate tummy. A baby’s gut flora (those good bacteria that play a huge role in keeping us healthy) is still forming during the first two to three years of life. This developing system can be more easily thrown off balance, leading to a higher risk of coming down with a foodborne illness (2,3).

What are the 3 major causes of foodborne illness?

Bacteria, viruses, and parasites make up the three main causes of all foodborne illness. Let’s go through the basics of each to better understand the risks associated with them.

Remember, food poisoning is another type of foodborne illness. It is separate from these three main causes as it results from a toxin created by germs — not the germ itself (which is the case for the following 3 causes).

#1: Bacteria

Bacteria like Salmonella, Listeria, Campylobacter, and E. coli are among the most common culprits behind foodborne illness in infants. These bacteria can be found in contaminated foods or surfaces and pose a serious risk to babies.

Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea, and fever. Since your baby’s body can’t fight off infections as effectively as adults, these bacterial infections can sometimes lead to severe complications.

#2: Viruses

Foodborne viruses, such as norovirus and hepatitis A, can also trigger illness in babies. These viruses are highly contagious and can spread through contaminated food, water, or surfaces.

Even a tiny amount of contaminated food can cause illness in infants, with symptoms ranging from stomach upset to more severe gastrointestinal distress.

#3: Parasites

Parasites, like Toxoplasma found in contaminated, raw, or undercooked meat, can infect both adults and infants, but the effects on babies can be especially concerning.

Though less common than bacterial or viral infections, parasites can have lasting impacts on an infant’s health, leading to symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, and weight loss. Furthermore, symptoms may linger if not addressed (4).

High-risk foods

Certain foods are more likely to carry these harmful germs and are best avoided or carefully handled when you prepare food for your baby (5).

While they all have a general recommendation from governing bodies, like the CDC and Health Canada, to wait until 5 years of age to introduce foods that fall under these categories, we have a slightly different perspective at My Little Eater.

My Little Eater

Recommendation

Recommendation

While considering the risk of introducing these foods too early, we also encourage you to consider the benefits of introducing foods like sushi, over-easy eggs, soft cheeses like brie, etc. to your child before 5 years of age.

We see the benefits of exposure to a variety of flavors and textures from these foods as outweighing the very low risk of contracting a severe infection from them.

We know that multiple exposures are key to getting your child to learn to like a new food, and that toddlers typically have a fear of new foods (called neophobia). The longer you wait to introduce various foods, the more hesitant they’ll be to try them, and the more likely it is that the food will be rejected.

We would never suggest offering these high-risk foods to babies under 12 months old because, at that age, the risk outweighs the benefit. But as they get older, we do think that the benefits begin to outweigh the risks and suggest introducing some of these foods ahead of 5 years old.

Since we do not know your child’s medical history, we always recommend speaking with their pediatrician to make the most informed choice that you can and ensure that your child’s unique medical needs are considered when doing so.

Raw or undercooked poultry, meat, and seafood

Foods like sushi, raw oysters, or even rare-cooked meats can carry harmful bacteria and parasites.

For babies and young children, it’s recommended to cook raw meat, poultry, and seafood thoroughly to reduce the risk of exposure to bacteria like Salmonella and Listeria or to parasites like Echinococcus and Taenia (6,7).

Unpasteurized dairy products

Unpasteurized milk, cheese, and yogurt can be a breeding ground for bacteria, especially Listeria, which can be extremely dangerous for young children.

A 2017 study found that unpasteurized dairy products are significantly riskier than pasteurized ones, causing 840 times more illnesses and 45 times more hospitalizations (8).

In 1991, Canada’s Food and Drug Regulations prohibited the sale of raw milk to protect against foodborne illnesses such as E. coli (9). More recently, California issued a voluntary recall of all raw milk and cream products from Raw Farm, LLC due to potential bird flu contamination (10).

When buying dairy products for babies and young children, always read ingredient labels to ensure you’re purchasing pasteurized dairy products.

Risky Choices

- Raw (unpasteurized) milk.

- Soft cheeses made from unpasteurized milk (like brie, blue cheese, queso fresco, or camembert).

Safer Choices

- Pasteurized milk.

- Hard cheeses such as cheddar and Swiss.

- Pasteurized soft cheeses (look for the label on cheeses like brie, camembert, etc.).

- Cottage cheese, cream cheese, string cheese, or feta. These cheeses almost always use pasteurized milk in processing.

Unpasteurized juice

Unpasteurized juice or cider can be contaminated with bacteria and viruses such as Salmonella and E. coli (11). The various fruits used to make juice may become contaminated on the farm or during processing, so pasteurization is needed (11).

If you choose to purchase unpasteurized juice or cider, bring it to a rolling boil for at least 1 minute before drinking.

Note: Most juices sold in Canada and the United States are pasteurized (21,22). Unpasteurized juice would likely be sold from juice bars, roadside stands, and farmer’s markets. Always be sure to check ingredient labels. If fresh juice has no label, ask the seller or avoid serving it to your child.

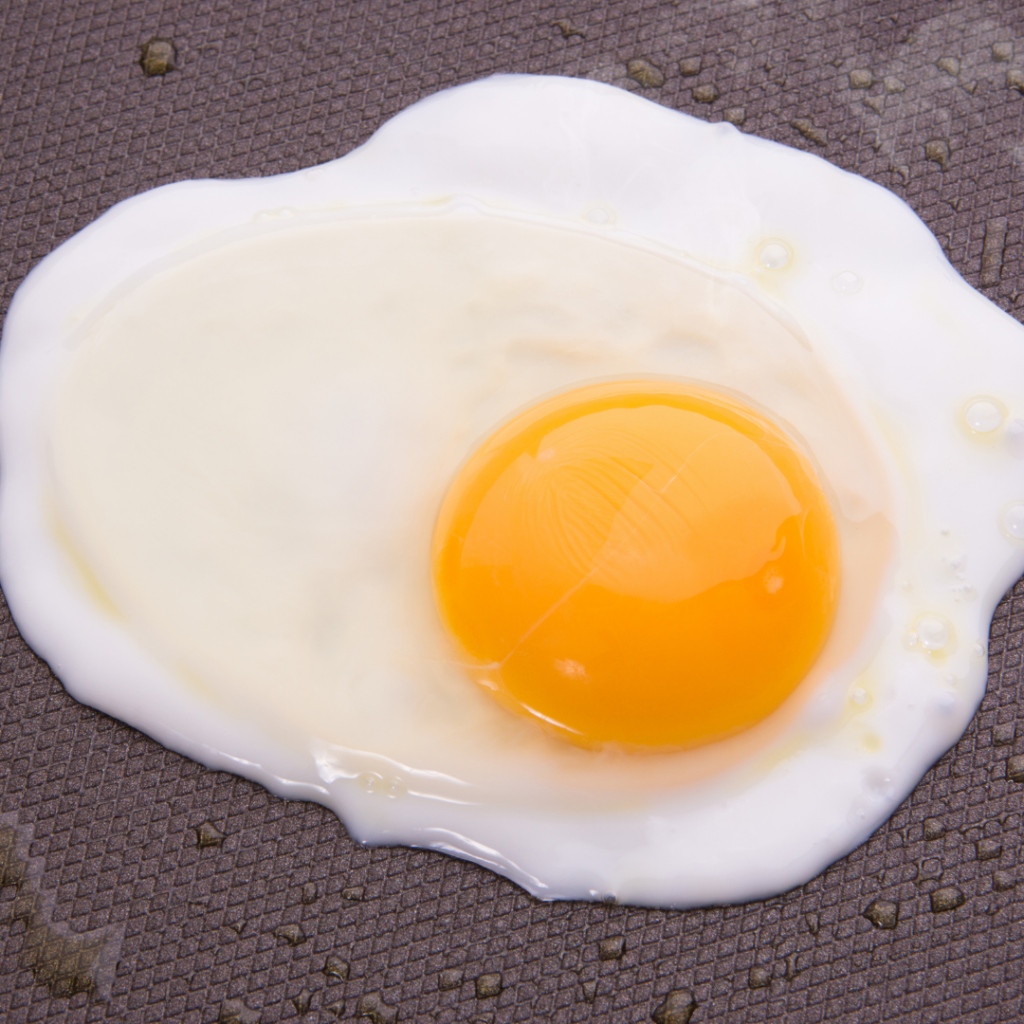

Raw or undercooked eggs

Raw or runny eggs can harbor Salmonella, a bacteria that can be particularly harmful to babies. It’s best to avoid raw eggs in dishes like homemade mayonnaise or uncooked dough, and always cook eggs thoroughly before offering them to your baby (both egg whites and yolk are firm).

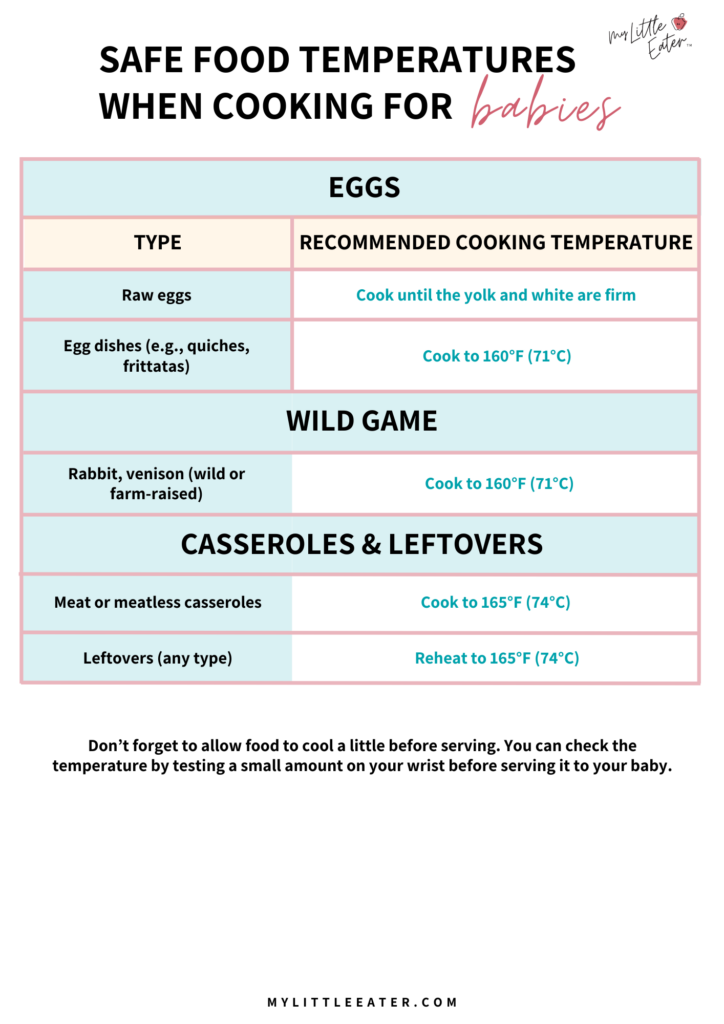

If serving a dish containing eggs, such as a quiche, frittata, or casserole, it needs to be cooked to 165°F if it contains meat, or 160°F without meat.

The one exception is eggs marked with the “British Lion” stamp, which are found in the UK and Europe.

These indicate that the hens had higher standards of care and were vaccinated against Salmonella (12). If you are able to get your hands on these, depending on where you live, you don’t have to worry about serving eggs with yolks that are a bit runny.

Uncooked flour

Flour is made from wheat, which grows in fields. As such, it can be contaminated with harmful bacteria such as Salmonella or E. coli from the soil, water, or animal waste (13).

Even though it undergoes processing to be created, flour is still considered a raw food and hasn’t been treated to kill any bacteria that it may contain (14). Therefore, flour needs to be cooked or baked thoroughly to kill any bacteria before serving it to your baby or young child.

If using flour in a recipe that will remain uncooked, look for heat-treated flour to ensure it will be safe. If you’re purchasing ready-made products, look for labelling that indicates that the food is edible when raw or uncooked.

This also applies to raw flour used in children’s play, such as homemade play dough that uses flour as an ingredient (14). Even if they don’t eat it, it can get on their hands and later find its way into their mouths.

Important note

For any uncooked grains, it’s best to check if they’ve been heat-treated before blending to use as a flour in uncooked food recipes or when used in activities like homemade playdough, sensory bins, etc. This is in case your little one puts their hands in their mouth after touching the raw grains.

Honey

Honey is a popular natural sweetener, but it carries a high risk of a very dangerous illness – botulism – for children younger than one year old (15).

Infant botulism can cause serious health issues, so it’s recommended to avoid all types of honey entirely for the first 12 months of life. This includes both pasteurized and unpasteurized honey as both may contain the bacteria Clostridium botulinum that can cause infant botulism (15).

This recommendation also includes both cooked and uncooked products made with honey, as even cooking at high temperatures is not enough to kill off the bacteria. For example, even though honey-flavored Cheerios are processed and made at high temperatures, they still need to be avoided for babies under 12 months old.

Most cases of infant botulism occur before 6 months of age as an infant’s immune system is not fully developed and is not able to defend against this bacteria (16,17). If an infant ingests honey containing C. botulinum, it can grow into bacteria in the gut that release toxins that can cause paralysis (16).

A buffer of waiting until 12 months allows your baby’s digestive tract to mature and develop (17). After your child’s first birthday, the risk of developing infant botulism is low because they have developed natural defenses against it. These include good bacteria in their intestines to protect against C. botulinum and prevent it from growing and releasing toxins (15).

Major governing bodies unfortunately don’t specify or give guidance on whether unpasteurized honey can be given to children 12+ months. Instead, they just say “honey” in general is okay after 12 months.

So of course, we started to dig deeper!

What we found is that after 12 months of age, children can have either pasteurized or unpasteurized honey. This is because the pasteurization process for honey is not done for the same food safety reasons as it is with foods such as milk, which uses it to kill harmful bacteria (18,19).

Honey has a low moisture content and high acidity, meaning most bacteria can’t live there (18). Honey pasteurization is mainly done to prevent crystallization, prolong the shelf-life, and create a more visually appealing product (18,19).

Always make the choice that works best for you based on your family values, preferences, and comfort level.

Unwashed fruits or vegetables

Always wash any fruit or vegetable before cooking or serving it raw – even vegetables with inedible rinds! This is because bacteria and other germs can be transferred from the outside of the fruit or veggie to the inside, edible portion, while it is being cut or prepared for cooking.

For example, melons cannot be left at room temperature for longer than 2 hours after they’ve been cut (only 1 hour if the room temperature is above 90°F). This is because bacteria can be transferred from the outer rind to the inner flesh when it is cut open, and the heat allows this bacteria to multiply rapidly (20). For this reason, cut melons should be refrigerated immediately and stored for no more than 7 days.

Additionally, certain vegetables are more prone to bacterial contamination, such as raw or undercooked sprouts (ie. alfalfa or bean sprouts) and raw fiddleheads. To reduce the risk, thoroughly wash and cook these foods until steaming hot before serving them to your child. Be sure to wash your hands thoroughly after handling them raw as well.

How to prevent food poisoning and other foodborne illnesses at home

We know this is a lot to process, but the good news is foodborne illness is very preventable. Here are our top tips for keeping your little one safe!

Tip #1: Practice cleanliness

Always wash your hands thoroughly before preparing food for your baby. Clean countertops, cutting boards, and utensils after handling raw foods, especially meats and eggs (following standard food safety recommendations). Harmful bacteria can linger on surfaces and transfer to other foods.

Tip #2: Separate raw and cooked foods

Avoid cross-contamination by keeping raw foods separate from those that are ready to eat. For example, if you’re preparing raw meat, use a dedicated cutting board and keep it away from other foods you plan to serve to your baby.

Tip #3: Cook foods thoroughly

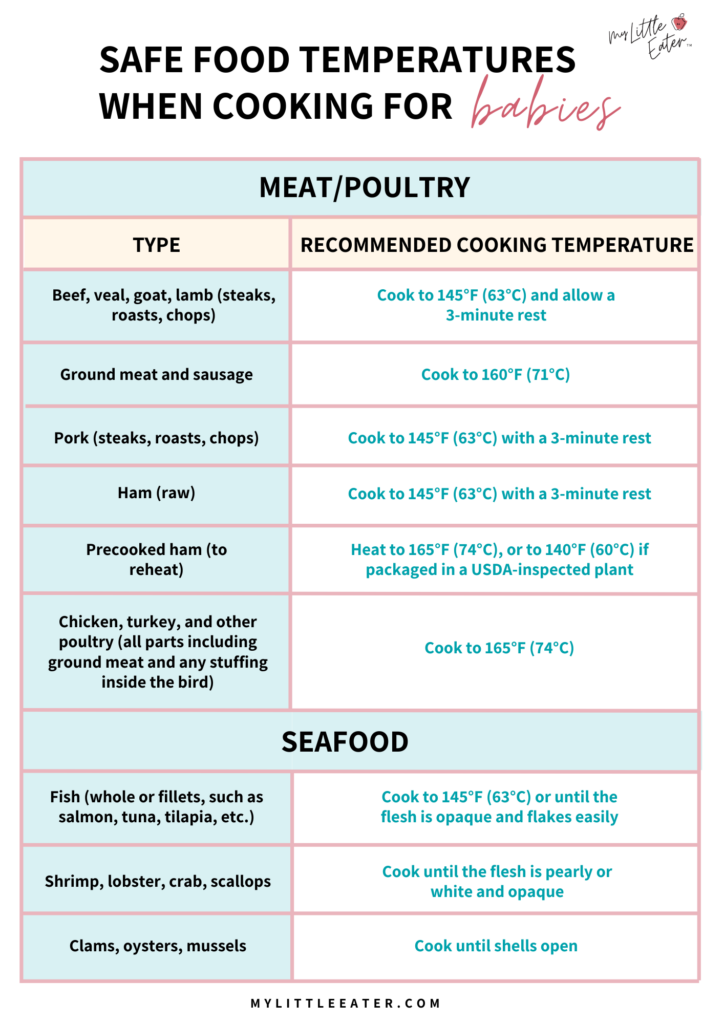

As discussed, undercooked foods like meat, poultry, and eggs, can harbor bacteria like Salmonella and E. coli. Be sure to cook foods to the recommended safe temperatures to kill off any harmful germs.

We recommend using a thermometer to check a food’s temperature when possible, instead of relying solely on appearance.

Below are the recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for safe cooking temperatures to help ensure your meals are prepared safely for your baby (23).

Click on either image to download both automatically and save for future reference!

Tip #4: Store food safely

Refrigerate perishable items promptly and avoid leaving prepared foods out for extended periods. It’s best to throw away leftovers after one to two days to minimize the risk of spoilage.

Breast milk requires careful storage to prevent the growth of harmful bacteria. Breast milk can be left at room temperature if it will be consumed within 4 hours. When refrigerated, it can remain safe for 4 days, and if frozen, it lasts for about 6 to 12 months (24).

Anything beyond these timelines is not safe and can lead to foodborne illnesses.

For formula-fed babies, it’s important to thoroughly read the instructions on your baby’s formula package. For most products, once the formula has been mixed, it will only last for 24 hours in the fridge or 2 hours at room temperature (25).

If your baby has taken a drink from it, you can no longer store it in the fridge and it will only last for 2 hours from the start of the feeding (25). All leftovers must be discarded (25).

It’s important to follow these rules carefully because the vast nutrition in formula (including being protein-rich) combined with its moisture, creates the perfect “food” for bacteria to breed and multiply once prepared and when left out of the fridge (26). This makes it risky for your baby to consume past these time frames (26).

Tip #5: Check for food recalls

Stay updated on food recalls, especially for items popular with children. Sometimes foods are recalled due to harmful bacteria like Listeria or Salmonella.

For the latest information and resources on recalled products, check the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website.

What are the first signs of foodborne illness?

Babies can’t tell us how they feel, so it’s important that you’re able to recognize the subtle signs that may indicate foodborne illness (and they are very similar to other gastrointestinal infections so it may take a while to realize the cause or you may never know!).

If this worries you and you’re now thinking “How will I ever tell if my baby has a stomach bug or foodborne illness?”…don’t stress too much!

For most mild to moderate cases, the symptoms will be similar to other stomach bugs and can mostly be treated at home in the same way other illnesses are. We want to focus on treating the symptoms – not worrying about the cause. Check out our blog on what to feed a sick baby for more on this.

If you notice any of the symptoms below, keep a close eye on your baby and monitor for worsening signs. Specifically, watch for signs of dehydration which can develop quickly in babies and young children from vomiting and diarrhea (27).

If symptoms seem to get worse, or persist for longer than 3 days, seek medical attention.

Vomiting

Sudden vomiting can often be an early indicator of a foodborne illness. Babies may seem unsettled, and you may notice more frequent or forceful spit-ups than usual.

While occasional spit-up is normal, repeated vomiting – especially if it’s paired with other symptoms – could be a sign of foodborne illness.

Diarrhea

Loose, watery stools that appear more frequently than usual can signal a digestive issue. Diarrhea in babies is especially concerning as it can lead to severe dehydration quickly, which is dangerous for young children.

If you notice diarrhea accompanied by a foul smell or unusual color, it’s worth checking in with your pediatrician.

Fussiness and Crying

Changes in your baby’s behavior can be a big clue that something is wrong. If your little one suddenly becomes extra fussy, cries more than usual, or seems uncomfortable—especially after eating—they might be feeling the discomfort associated with foodborne illness.

Fever

A fever is the body’s natural response to infection and a signal that the immune system is fighting off something harmful. In cases of foodborne illness, a mild to moderate fever may develop as the baby’s body attempts to battle the harmful germs (bacteria or viruses) causing the infection.

Reduced Appetite and Lethargy

Babies suffering from a foodborne illness may feel too unwell to eat and may seem more tired or lethargic than usual. If your typically energetic baby suddenly becomes unusually sleepy or doesn’t want to feed, it’s a good idea to keep an eye on them for other symptoms.

Belly pains or cramping

One of the earliest signs of foodborne illness in babies is belly pain or cramps. If your baby starts crying inconsolably, arching their back, or pulling their legs toward their stomach, it could be a sign that they’re experiencing stomach discomfort.

Dehydration

Dehydration is a serious concern with foodborne illness in babies, especially if vomiting or diarrhea is involved. Keep an eye out for signs of dehydration, such as a dry mouth, fewer wet diapers, crying with little to no tears, sunken eyes or fontanel, or unusual lethargy.

If you suspect your baby is dehydrated, offer small amounts of fluids frequently, and seek medical attention as soon as possible.

Treatment for foodborne illnesses in babies

Foodborne illness (including food poisoning) treated at home without medical intervention is not uncommon for mild cases and the illness often naturally resolves on its own. However, in severe cases involving dehydration and worsening or persisting symptoms, it is best managed in the hospital.

How to manage symptoms at home

Prioritize Hydration

Babies lose fluids quickly through vomiting and diarrhea, which can lead to dehydration. Keep them hydrated by offering small sips of water or oral rehydration solutions (ORS) specifically formulated for children such as Pedialyte. These contain the right balance of salts and sugars to replenish lost fluids.

If your baby is under 12 months old, be sure to confirm with their pediatrician before offering solutions like Pedialyte.

For breastfed babies, continue breastfeeding as breast milk contains antibodies and nutrients that can help support recovery.

For formula-fed babies under 12 months old, continue offering bottles of formula. You may notice that they need smaller bottles more frequently due to a decrease in appetite, this is ok. We don’t want to be pushing too much water, formula will hydrate them, so we recommend offering small amounts more frequently.

Offer Gentle Foods Slowly

After the vomiting subsides and your baby seems interested in eating, you can try introducing mild foods gradually. You may want to start with soft and easy-to-eat options like plain cereal, mashed potatoes, yogurt, applesauce, oatmeal, or bananas, avoiding any fatty or spicy foods that may upset a still-sensitive stomach.

Some babies’ appetites may come back slowly. Don’t stress – it can take a few days to even a week for their appetite to return.

However, some babies and toddlers bounce back quickly and if they seem up for what they would typically eat, it’s ok to offer it – bland foods are not always required. In fact, the best advice we have for you is to keep to their regular feeding schedule and make sure to go back to offering variety as soon as possible.

Learn more about what to feed your sick baby and toddler during and after an illness.

Babies too young to have solid foods don’t usually need any changes to their feeding schedule except for a possible increase in frequency to accommodate smaller “meals”. Older babies that do eat solids may forego solids completely while symptomatic and instead rely on nutrition and hydration from breast milk or formula until feeling better.

We recommend that you continue to offer it at regular mealtimes as you typically would, but understand that they may not eat any of it while still experiencing symptoms.

Watch for Diaper Rash

Frequent diarrhea can cause painful diaper rashes. Change diapers promptly and apply a gentle diaper cream to protect your baby’s skin. Letting their skin air-dry between changes can also help reduce irritation.

Provide Comfort and Rest

Foodborne illnesses can leave babies feeling exhausted and fussy. Holding, rocking, or gently massaging their tummy can help them relax and feel comforted.

Sleep is essential, so encourage as much rest as possible, which allows their body to focus on healing.

How long do foodborne illnesses last?

For most babies, symptoms of food poisoning or other foodborne illnesses, like vomiting and diarrhea, last about 1 to 3 days. Some cases might extend to one week, especially if dehydration or a sensitive tummy prolongs recovery.

Keep in mind that every baby is different; some may bounce back quickly, while others need a little more time to regain their usual energy and appetite.

When to seek medical attention

While mild cases can be managed at home, some signs indicate that medical care is necessary. These signs include:

- Persistent vomiting or diarrhea: If vomiting or diarrhea continues for more than a couple of days or is so frequent that your baby can’t keep down any fluids, they’re at risk for dehydration.

- High fever: A fever over 100.4°F (38°C) in babies under three months or over 102°F (39°C) in older infants should be checked out by a healthcare provider.

- Blood in vomit or stool: This can be a sign of a more serious infection and should be evaluated by a doctor.

- Extreme drowsiness or irritability: If your baby seems unusually hard to wake, lethargic, or extremely fussy, it’s a good idea to seek medical advice.

Pin it to save for later

References

- USDA. What is the difference between food poisoning and foodborne illness? Retrieved from: https://ask.usda.gov/s/article/What-is-the-difference-between-food-poisoning-and-foodborne-illness

- Buonocore, G. (2024). Microbiota and gut immunity in infants and young children. Global Pediatrics, 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpeds.2024.100202

- Hill, C.J., Lynch, D.B., Murphy, K. et al. (2017). Evolution of gut microbiota composition from birth to 24 weeks in the INFANTMET Cohort. Microbiome 5, (4). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0213-y

- USDA. Parasites and foodborne illness. Retrieved from: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/foodborne-illness-and-disease/illnesses-and-pathogens/parasites-and-foodborne-illness-0

- Department of Health. Causes and symptoms of foodborne illness. Retrieved from: https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/foodborne/basics.html

- CDC. Safer food choices from children under 5 years old. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/food-safety/foods/children-under-5.html

- Government of Canada. Food safety for vulnerable populations. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-safety-vulnerable-populations/food-safety-vulnerable-populations.html

- Costard, S., Espejo, L., Groenendaal, H., & Zagmutt, F. J. (2017). Outbreak-Related Disease Burden Associated with Consumption of Unpasteurized Cow’s Milk and Cheese, United States, 2009–2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(6), 957-964. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2306.151603.

- Silveira, A., Carvalho, J. P., Loh, L., & Benusic, M. (2023). Public health risks of raw milk consuption: Lessons from a case of paediatric hemolytic uremic syndrome. CCDR, 49(9). Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/canada-communicable-disease-report-ccdr/monthly-issue/2023-49/issue-9-september-2023/raw-milk-consumption-paediatric-hemolytic-uremic-syndrome.html

- California Department of Public Health. State secures broad voluntary recall of raw milk and cream to protect consumers. Retrieved from: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/OPA/Pages/NR24-044.aspx

- Government of Canada. Potential risks of drinking unpasteurized juice and cider. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-safety-fruits-vegetables/unpasteurized-juice-cider.html

- Egg Info. British Lion eggs. Retrieved from: https://www.egginfo.co.uk/british-lion-eggs

- Government of Canada. Safe handling of flour. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/general-food-safety-tips/safe-handling-flour.html

- FDA. Flour is a raw food and other safety facts. Retrieved from: https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/flour-raw-food-and-other-safety-facts

- Government of Canada. Infant botulism. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-safety-vulnerable-populations/infant-botulism.html

- World Health Organization. Botulism. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/botulism

- Cleveland Clinic. When your baby can have honey. Retrieved from: https://health.clevelandclinic.org/when-is-it-safe-to-give-honey-to-my-baby

- Ontario Honey. Unpasteurized vs pasteurized honey. Retrieved from: https://www.ontariohoney.ca/all-about-honey/honey-pasteurization

- Club House. Pasteurized vs unpasteurized honey: What’s the difference and are both safe to eat? Retrieved from: https://www.clubhouse.ca/en-ca/articles/pasteurized-vs-unpasteurized-honey

- Government of Canada. Food safety tips for melons. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-safety-fruits-vegetables/melons.html

- FDA. What you need to know about juice safety. Retrieved from: https://www.fda.gov/food/buy-store-serve-safe-food/what-you-need-know-about-juice-safety

- Health Canada. Unpasteurized fruit juices and cider – now what you are drinking. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-safety/information-product/unpasteurized-fruit-juices-cider-know-what-you-drinking.html

- Foodsafety.gov. Cook to a safe minimum internal temperature. Retrieved from: https://www.foodsafety.gov/food-safety-charts/safe-minimum-internal-temperatures

- CDC. Breast milk storage and preparation. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breast-milk-preparation-and-storage/handling-breastmilk.html

- Government of Canada. Preparing and handling powdered infant formula. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/milk-infant-formula/preparing-handling-powdered-infant-formula.html

- Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. What conditions encourage bacteria to grow? Retrieved from: https://www.fdacs.gov/Consumer-Resources/Health-and-Safety/Food-Safety-FAQ/What-conditions-encourage-bacteria-to-grow

- Mayo Clinic. Food poisoning. Retrieved from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/food-poisoning/symptoms-causes/syc-20356230

Edwena Kennedy, RD

Founder and lead Registered Pediatric Dietitian at My Little Eater Inc., creator of The Texture Timeline™, and mom of two picky-turned-adventurous eaters.

Edwena Kennedy, RD

Founder and lead Registered Pediatric Dietitian at My Little Eater Inc., creator of The Texture Timeline™, and mom of two picky-turned-adventurous eaters.

Jillian Smith, RD

Registered Dietitian at My Little Eater Inc., and dog-mom to River. Jillian works behind the scenes answering nutrition questions and supporting parents of babies and toddlers to feed their little ones with confidence.

She offers parents one-on-one support through counselling sessions. Click below to book a free 15-minute Discovery Call with her today!

Jillian Smith, RD

Registered Dietitian at My Little Eater Inc., and dog-mom to River. Jillian works behind the scenes answering nutrition questions and supporting parents of babies and toddlers to feed their little ones with confidence.

She offers parents one-on-one support through counselling sessions. Click below to book a free 15-minute Discovery Call with her today!