- No Comments

- Bianca Gruenewald, RD

- Originally Published: January 14, 2020

For many parents, the thought of giving their baby a food that could result in an allergic reaction is downright terrifying. And those fears are completely valid!

That’s why we’re going to cover everything you need to know about safely introducing allergenic foods to your baby. This includes when to introduce them, how to introduce them, and what to do if an allergic reaction does happen.

Our goal is to ease your fears and help introduce your baby to allergenic foods with confidence.

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways

- Early introduction of allergenic foods is the best way to minimize your baby’s risk of developing an allergy.

- Before introducing allergens to your baby, it’s important to know the signs and symptoms of an allergic reaction and what to do if one occurs.

- Start introducing allergens to your baby early, beginning right at the time of starting solids (around 6 months of age).

- Ideally, all allergens should be introduced before your baby’s first birthday.

- Once you’ve ruled out a food as an allergy, continue to offer it often (aiming for at least once per week).

Table of Contents

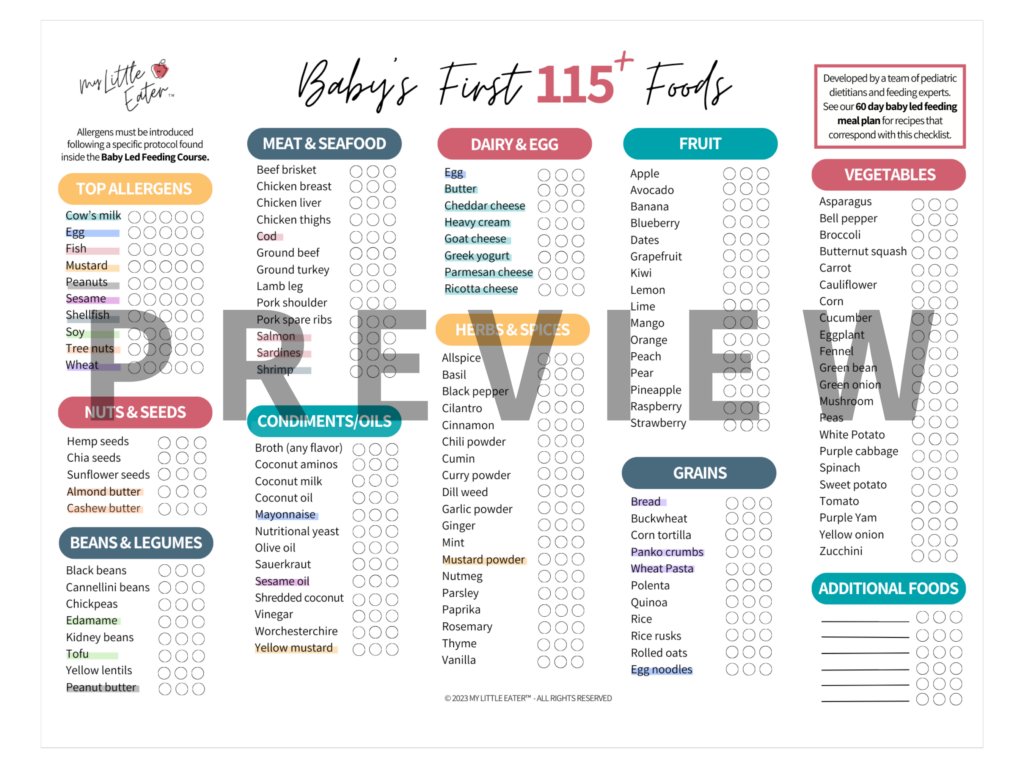

Top allergenic foods

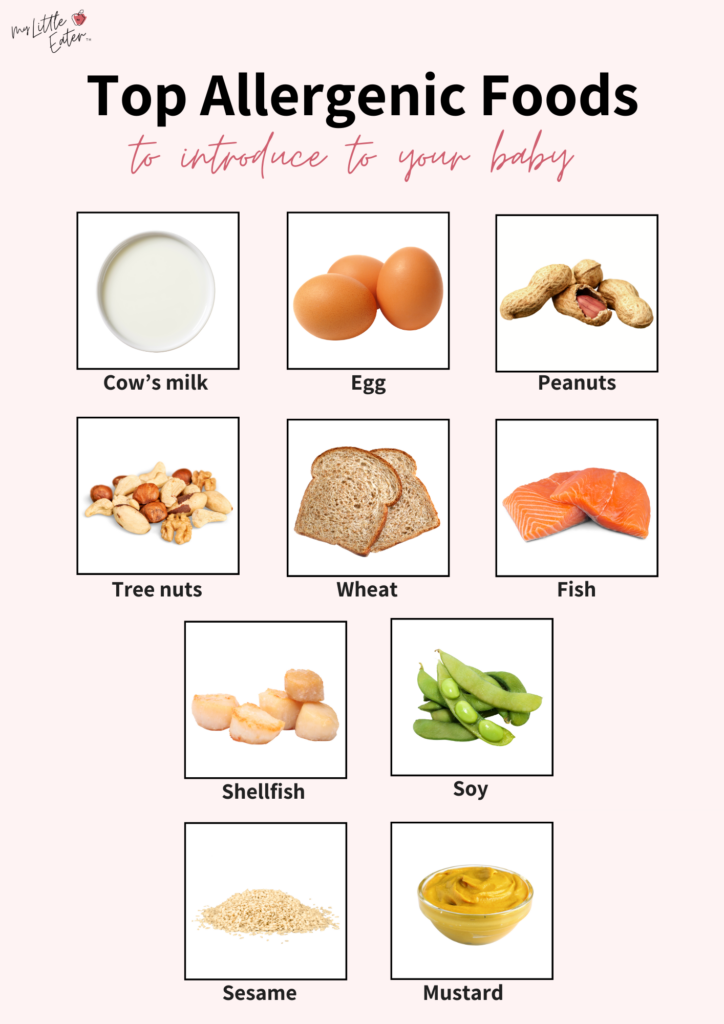

It’s estimated that approximately 1 in 13 children in the United States have a food allergy (1). While it’s technically possible to be allergic to any food, each country has a list of top allergens which varies depending on how common each food allergy is in that area of the world (2).

In Canada, there are 11 top allergens (3):

- Cow’s milk

- Eggs

- Peanuts

- Tree nuts (common tree nuts include: almonds, cashews, hazelnuts, macadamia nuts, pecans, pine nuts, pistachios, walnuts, Brazil nuts).

- Wheat

- Finned fish

- Shellfish (crustaceans and mollusks)

- Soy

- Sesame

- Mustard

- Sulphites

Note: Sulphites are found as a preservative ingredient in some packaged foods. Although sulphites are not considered a true food allergy, they are included in the list of priority food allergens in Canada because they can produce allergy-like symptoms in individuals who are sensitive (4).

That being said, since they’re not a true food allergen, it’s not necessary to follow the typical allergen introduction protocol for sulphites.

The top food allergens in the United States (U.S.) are very similar, except that they do not include mollusk shellfish, mustard, or sulphites (5).

Be sure to review your country’s list of priority allergens before starting solids with your baby.

Importance of early allergen introduction

It was once thought that the introduction of allergens should be delayed until at least 1 year of age. However, this recommendation was made only on expert opinion and tradition and was not evidence-based (6,7,8).

In 2015, the way that experts thought about allergies changed. A revolutionary study called “Learning Early About Peanut Allergy” (LEAP) was published, providing new insights into how the introduction of allergenic foods should be handled.

This study showed that introducing peanuts to high-risk babies between 4-11 months of age reduced their risk of developing a peanut allergy by 81% (9). This is compared to the group of high-risk babies that delayed the introduction of peanuts (9).

In fact, more research has since been done on this topic and has shown that delaying the introduction of allergens can actually increase the risk of developing an allergy, not prevent it (7,10,6).

The reason for this is that when you introduce common food allergens early, it allows your baby’s immune system to develop a tolerance to the proteins in those foods. This makes them less likely to react to it as an allergen when they eat it in the future (11).

The research in this area continues to grow and evolve, but many major health organizations now agree that introducing babies to allergenic foods early is the best strategy for food allergy prevention. This is true for not only peanuts, but for all top allergenic foods (10,12,13,14).

When to introduce allergens

We’ve covered why introducing allergens early is important, but how early are we talking here?

You should begin the process of introducing allergens as soon as possible when your baby starts solids and is showing all of the developmental signs of readiness to begin. For most babies, this will be right around 6 months of age.

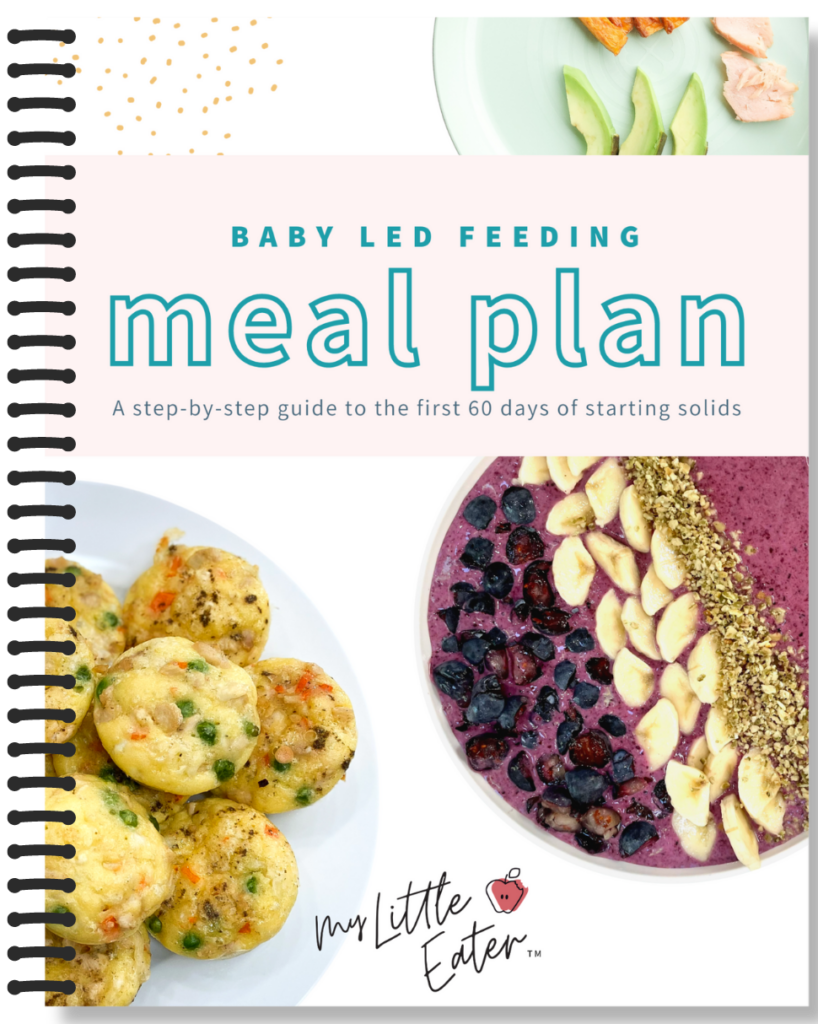

If the process is started early, you can easily get through introducing all of the top allergens at least twice within the first 3 months of starting solids (our 60-Day Baby Led Feeding Meal Plan walks you through exactly how to do that in the safest, most logical way).

At the very least, all priority allergens should be introduced before your baby’s first birthday.

That being said, there are some specific cases where it may be beneficial to introduce allergens a bit earlier. For babies at high risk of developing an allergy, there’s evidence to show that introducing allergens between 4-6 months may be helpful for allergy prevention (15).

Defining high risk

Your baby is considered to be at high risk of developing a food allergy if they have severe eczema or a known, pre-existing food allergy (10,15,16). In both cases, your baby may benefit from being introduced to top allergens earlier than what is suggested for most, meaning between 4-6 months of age (16).

If you’re unsure if your baby is considered to be high risk and you’d like to know whether you should introduce allergens early, seek the advice of your baby’s pediatrician or primary care doctor.

Note: The introduction of allergens between 4-6 months should still be guided by your baby’s developmental readiness and ability to consume food safely (15).

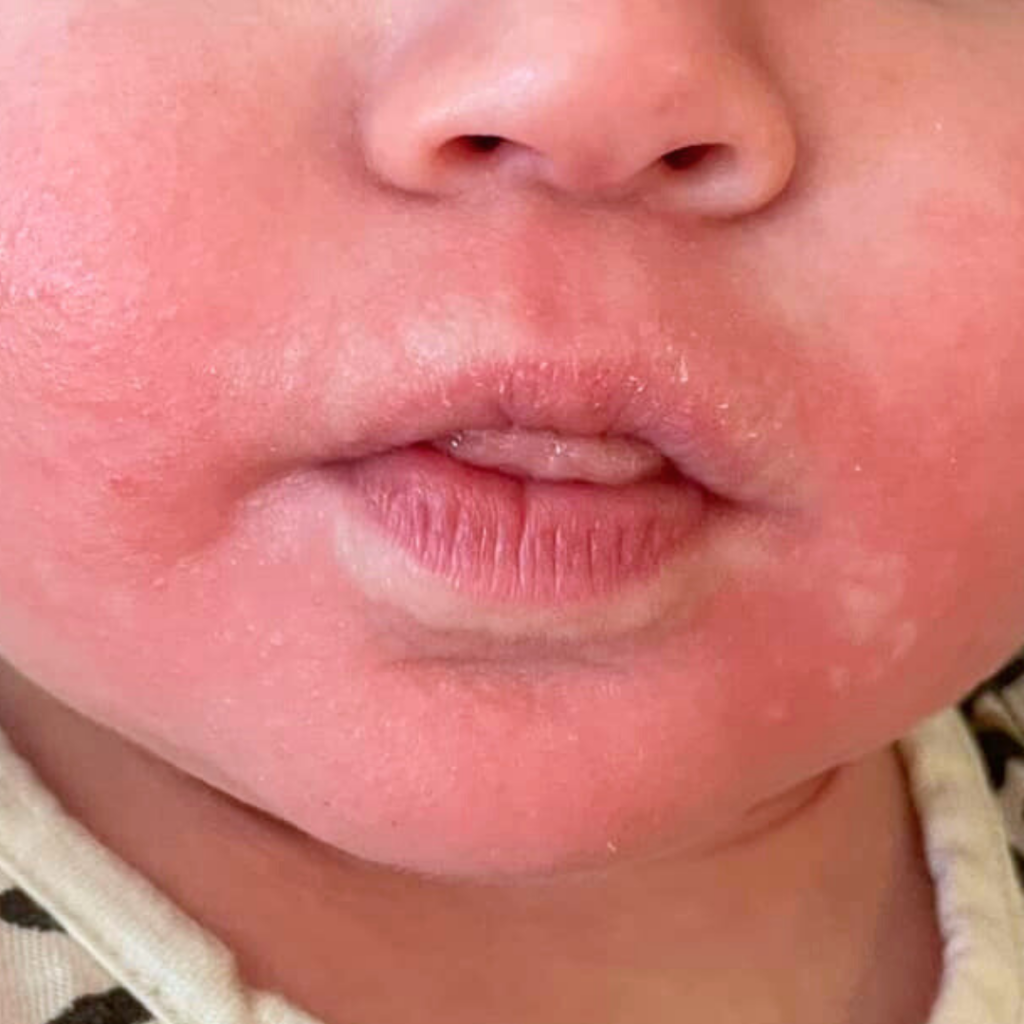

Severe eczema

Eczema is an inflammatory skin condition that causes red, scaly rashes to appear on the skin (16,17,18). Severe eczema interferes with the skin’s natural protective barrier, which is thought to make babies more vulnerable to developing an allergy (17,18).

There is no standardized definition for what classifies eczema as severe. Generally, eczema can be considered severe when rashes are widespread and symptoms are long-lasting.

Severe eczema may also be judged by the intensity of the rash. This can be determined by factors like the level of redness and the presence or intensity of elevated bumps or blisters on the skin (17,18).

Babies with mild to moderate eczema (as determined by their pediatrician) may still be at an increased risk for developing a food allergy. However, unlike those with severe eczema, it is not recommended to introduce allergenic foods any earlier than 6 months (15,19).

Pre-existing food allergy

Babies who already have a known food allergy are at a higher risk for developing an allergy to another food (16).

If your baby has already experienced an allergic reaction to a food and you have not seen an allergist yet, we recommend that you do so. Allergists may perform blood or skin testing, and may even do a supervised oral food challenge in their office, to help determine what other foods they may be allergic to. From there, they can give you a clear plan on how to move forward.

Family history

Some organizations, like the Canadian Pediatric Society, suggest that having a first-degree relative (parent or sibling) with a food allergy, severe eczema, or asthma is one of the factors that puts babies into the category of high risk (15).

However, there is research to suggest that a family history may not play as much of a role as we once thought in a baby’s risk of developing a food allergy, especially amongst siblings (20).

If your baby has a first-degree relative with a food allergy, asthma, or severe eczema, we suggest speaking to an allergist early on. Check whether or not they recommend that you introduce allergens to your baby early (between 4-6 months) based on their full medical history, other factors of risk, and the guidelines where you live.

What you need to know before introducing allergens

Before we dive into the protocol for how to introduce allergens, there are a few things that we want you to be aware of.

How to recognize mild vs. severe allergic reactions

It’s important to know the difference between mild and severe reactions to identify when symptoms warrant simply stopping the meal, versus a more serious situation that requires immediate medical attention.

Mild and severe symptoms (and anything in between) typically show up within 2 hours of ingesting the food that has triggered a reaction.

Common symptoms of a mild allergic reaction include any ONE of the following (21):

- Nasal congestion

- Sneezing

- Watery eyes

- Mild itchy skin

- Mild redness of the skin

- A few mild hives (not spreading, isolated to one small area)

- Mild gastrointestinal symptoms (such as a single episode of vomiting or diarrhea)

What to do:

- Stop serving the food immediately and don’t offer it again until your baby can be seen by a medical professional.

- Ask your baby’s pediatrician or primary care physician to refer you to see an allergist, who will be able to provide you with the next steps.

If your baby shows more than one of the above symptoms, especially if it’s affecting multiple organ systems (skin, respiratory, digestive, etc.), this could mean a more severe reaction is taking place (22).

In this case, call 911 immediately and request that the paramedics bring an epinephrine auto-injector.

Common symptoms of a severe allergic reaction include (21):

- Widespread rash (redness, hives, or eczema)

- Severe swelling or itchiness of the lips, tongue, or throat

- Coughing or wheezing

- Trouble breathing

- Change in skin or lip color (pale, blue)

- Continuous vomiting or diarrhea

- Blood in the stool

- Lethargy (your baby suddenly appears very tired, weak, or limp)

If your baby experiences one or more of the above symptoms, they may be at risk of going into anaphylactic shock, which requires urgent medical attention.

What to do:

- Call 911 immediately and be sure to request that the paramedics bring an epinephrine auto-injector.

Other types of reactions with similar symptoms

It should be noted that there are other types of reactions that could occur when your baby eats a new food. This includes more delayed reactions (occurring 2+ hours after ingesting a food), food intolerances, and other less serious types of reactions.

Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis (FPIES)

FPIES is a delayed food reaction that occurs a few hours after eating a new food (23,24). A reaction can be triggered by foods in the baby’s diet that aren’t necessarily one of the top allergens mentioned earlier.

Symptoms can include one or more of the following:

- Projectile vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Extreme dehydration

- Lethargy

Oral allergy syndrome

Oral allergy syndrome, commonly known as OAS, is a type of allergic reaction associated with mild symptoms like itchiness or swelling of the mouth, face, lips, tongue, or throat (25). Symptoms usually occur within a few minutes but can appear up to an hour after eating (25).

While symptoms of OAS are most commonly mild, in rare cases, OAS may progress to severe swelling of the throat, difficulty breathing, or anaphylaxis (26). If your baby’s symptoms progress to any of the signs of a severe allergic reaction listed above, call 911 immediately and be sure to request that the paramedics bring an epinephrine auto-injector.

Food intolerance

A food intolerance is not the same as an allergy, because it does not involve the immune system. Rather, it involves the gastrointestinal system and occurs due to the lack of certain enzymes required to digest components of certain foods (27).

Symptoms include (27,28):

- Bloating

- Mild diarrhea

Intolerances are not as serious as allergies. But, if you suspect an intolerance, it’s still a good idea to stop offering the suspected trigger food until you can address your baby’s symptoms with your family doctor or pediatrician so that they can rule out an allergy or any underlying medical conditions.

The reason for this is that if your baby’s suspected intolerance turns out to be an allergy, allergic reactions can be much more severe the second time the trigger food is offered (29,30). So, it’s better to be safe than sorry and hold off on offering the suspected trigger food again in the meantime.

Contact dermatitis

If your baby develops a mild, red rash around their mouth and/or hands, they may be experiencing something called contact dermatitis.

It’s more commonly seen with foods that are more acidic (like citrus, kiwi, strawberry, pineapple, or tomato), or from spices that are reactive/irritating on the skin (like cinnamon or cayenne). Contact dermatitis is not harmful and should not cause any other symptoms (31).

Your baby’s rash is likely contact dermatitis and not an allergic reaction if the rash:

- Is only on the parts of your baby’s skin that were in direct contact with the acidic food.

- Is not spreading to other parts of the body.

- Goes away after you’ve cleaned your baby’s skin or within a couple of hours.

For more information on these other types of reactions, including FPIES, OAS, food intolerances, and contact dermatitis, check out our complete guide on introducing allergens.

How to introduce allergenic foods

Introduce when your baby is healthy

It’s important to introduce top allergens when your baby is healthy and free of symptoms so that you can clearly tell whether symptoms are from an allergic reaction or something pre-existing.

If your baby wakes up and is congested with a cold or showing signs of illness, it’s best to hold off and introduce the allergenic food when your baby is feeling better.

Introduce early in the day

Allergic reactions typically appear within 2 hours (or more) after eating. For this reason, it’s very important to introduce allergens early in the day to be able to carefully monitor your baby for symptoms after their meal (32).

Breakfast time is ideal but not mandatory! Just try to time it as early in the day as possible so that you’re not introducing a new allergen right before you put your baby down for the night.

Introduce only one new allergen at a time

To identify which food is potentially causing an allergy, introduce one new allergenic food at a time (8).

You can safely introduce allergenic foods alongside non-allergenic options (for example, pairing peanut butter with a banana), as the chance of reacting to a non-top allergen is very low.

Once an allergenic food has been ruled out as an allergen (using the protocol below), you can then treat it like any other food and serve it along with a new top allergen in the future!

How long to wait between introducing new allergens

Wait 24 hours after introducing one allergen before introducing a new one.

In the past, a common recommendation was to wait a few days between the introduction of new allergens to make it easier to distinguish which one caused a reaction, if one were to occur.

We now know that symptoms of an allergic reaction typically appear within 2 hours (or within a few hours in the case of FPIES), so a 24-hour buffer in between introducing new allergens is more than enough (30,32,33).

You can space out the introduction of new allergens by more than a day if you’d like. Just don’t delay the process too much.

Introduce using the proper protocol

It’s so important to follow an evidence-based protocol when introducing allergens to your baby, both for their safety and your peace of mind! So if you’re ready to get started, here’s how to do it.

Allergen introduction protocol

Step 1: Start small

- Offer your baby a small amount of the allergen (about 1/4 tsp).

- Wait 10 minutes while watching them closely for signs of an allergic reaction (your baby can munch on other non-allergenic foods while you wait).

- If no symptoms appear after 10 minutes, offer more of the allergenic food or allergen-containing meal, aiming for 2 tsp of the allergen in total.

Step 2: Monitor and record symptoms

Continue to monitor your baby closely for signs or symptoms of an allergic reaction for a few hours after the meal has ended (most symptoms will appear within two hours of eating) (32).

Tip: Since rashes caused by an allergic reaction can occur anywhere on the body, it can be helpful to remove your baby’s clothing down to their diaper while monitoring for symptoms so that you can clearly see if a rash develops.

While monitoring your baby, record details of the allergen introduction, making note of details like…

- Date and time of introduction

- Which allergen was introduced

- How the allergen was introduced (was the allergen offered alone or alongside any other foods)

- How much of the allergenic food was ingested

- Symptoms that occurred (if any)

- How symptoms changed and evolved as time went on (take photos and videos)

- Time of symptom onset and resolution

- Interventions used to ease symptoms (if any)

We include an allergen tracking cheat sheet in our guide on introducing allergens, which allows you to keep track of the details of each allergen introduction all in one place!

Step 3: Introduce the allergen for a second time

We recommend introducing the same allergen for a second time the day after the first introduction, to rule it out completely.

Allergic reactions tend to be mild on the first introduction and can be much worse the second time that the food is eaten (29,30). By introducing the allergen twice, this allows you to make sure there were no symptoms that may have been missed the first time around.

Step 4: Maintain exposure

After you rule out a food as an allergen, continue offering it regularly, as this will help your baby maintain their tolerance (30,34).

Aim to offer each ruled-out allergen at least once per week. Or if that isn’t possible, try to offer it at least a few times per month to reduce your baby’s chances of developing an allergy (10,35).

How much food counts as an exposure?

We recommend working up to serving about 2 tsp of an allergenic food to your baby during an exposure, however, this is just a guideline to aim for. There is no consensus on an exact dose that counts as an exposure to allergens.

If your baby eats a little bit less than this, there’s no need to stress! A little bit of an exposure is always better than nothing.

What to do if your baby won’t eat any of the allergenic food

If your little one refuses to eat barely any of the allergen you’re trying to introduce, simply try again the next day, repeating the same introduction protocol.

It’s completely normal for babies not to eat much when first starting solids. Your baby is still learning how to eat at this age, so they might not be consuming full meals right in the beginning. It’s important to keep this in mind when introducing allergens, too.

As frustrating as this can be, remember that your baby doesn’t realize that this meal has a specific purpose. It’s just another meal to them! Allergen introduction or not, we never recommend forcing your baby to eat anything.

To gently encourage your baby to eat the allergenic food, you can try things like modelling eating the food in front of them. Or letting them get messy and play with the food using their hands to help pique their interest.

Check out our other tips for encouraging your baby to eat solids.

Importance of seeing an allergist

Once you’ve taken the necessary steps during the reaction and your baby is out of immediate danger, we recommend scheduling an appointment with your baby’s pediatrician or primary care doctor as soon as possible.

They will be able to refer you to see an allergist who is equipped to perform an in-depth assessment on your child. This assessment may include skin or blood testing, and in some cases, an oral food challenge may be performed.

From there, the allergist will create an individualized plan regarding the allergen your baby reacted to, and the introduction of other allergens going forward.

Do not reintroduce the food that triggered the allergic reaction unless given instructions to do so by an allergist. If your baby has an allergy and you need help with how to meet their nutritional needs while avoiding that food, seek help from a Registered Dietitian.

Can babies outgrow allergies?

Yes, it is possible to outgrow an allergy. However, the chances of this happening vary depending on the allergen.

Cow’s milk protein allergy and egg allergy in particular have a much higher chance of being outgrown than other food allergies. For example, around 80% of babies with cow’s milk allergy will outgrow it by the time they reach age 14 (36). Similarly, around 70% of babies with egg allergy will outgrow it by the time they reach age 16 (37).

The treatment for most food allergies is strict avoidance, but because cow’s milk and egg allergies have a higher chance of being outgrown, allergists will sometimes propose another option for gradual exposure.

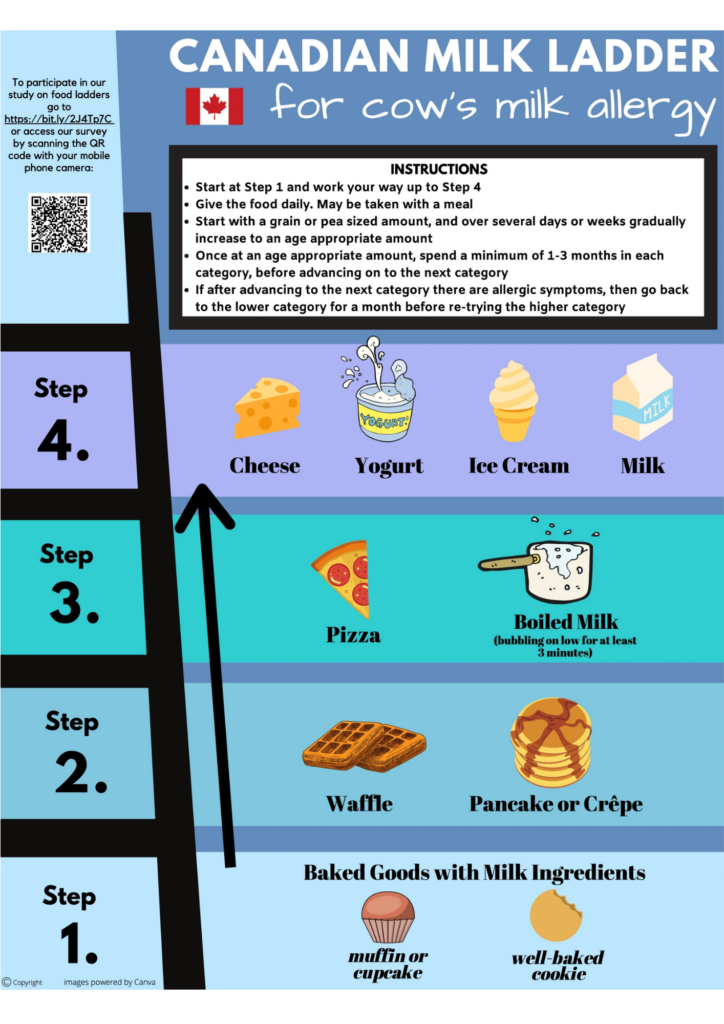

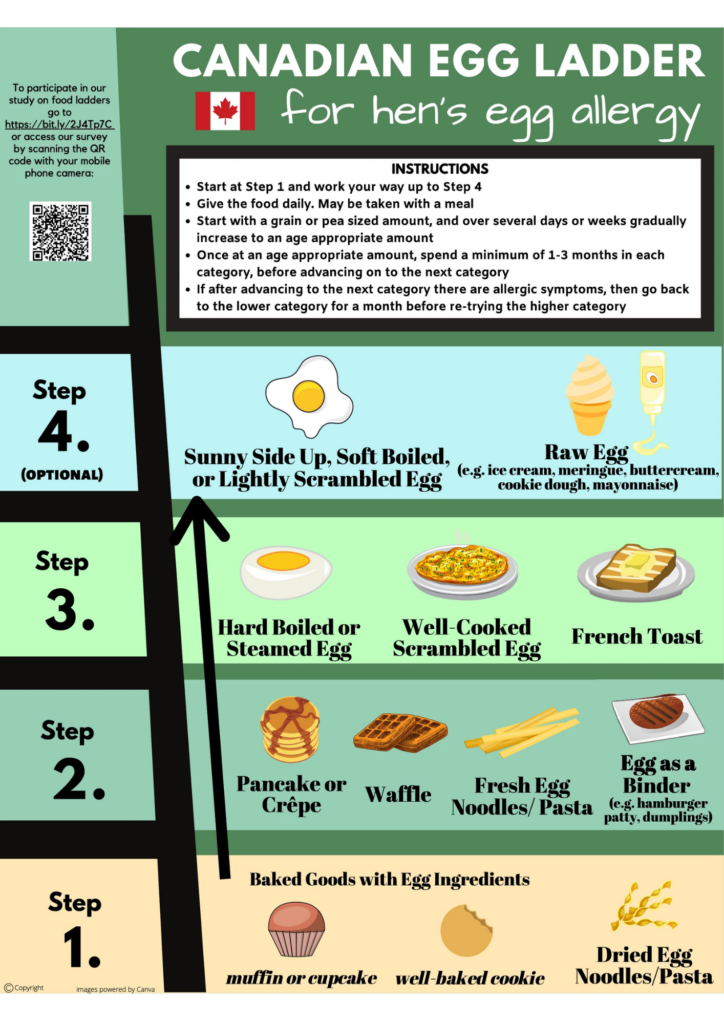

In these cases, the milk ladder and egg ladder are sometimes prescribed with the goal of gradually building up a tolerance to the allergenic food.

With these methods, a very small amount of milk or egg is reintroduced in a well-cooked form, such as a muffin. The cooking process changes the structure of the proteins that trigger allergic reactions, making it less likely for symptoms to occur (38).

As you move up the ladder, milk or egg is gradually offered in slightly larger amounts and in less cooked forms.

Important Note

Important Note

The milk and egg ladder should only be done under the advice of an allergist and after they have done appropriate testing to ensure that it’s safe to begin.

Those working through the milk or egg ladder should also receive regular follow-ups with an allergist and/or Registered Dietitian (39).

How to introduce a food that you’re allergic to

For most people, just being around a food and even touching it is not enough to cause an allergic reaction (32). Even so, we know this can be nerve-wracking to think about, plus there are exceptions!

If you know that you’re one of those people who are highly sensitive to your allergen, or you’d just like to play it safe, here are a few things that you can do to minimize your risk…

- Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and hot water after touching the allergenic food. Or wear rubber gloves while preparing and serving the food.

- Use soap and water to sanitize all kitchen surfaces, cutting boards, and dishware that have come into contact with the allergen.

- Wash your baby’s hands and face after the meal using a warm cloth to remove any residue.

- Wash the clothes that your baby was wearing during the meal.

- Lay a garbage bag on the floor underneath your baby’s high chair. This will make cleanup easier and eliminate the need for you to touch any of the allergenic food that has fallen on the ground.

If at this point you’re thinking to yourself… “That all sounds great, but I’m still way too scared!” – that’s ok too. An alternative is to arrange for a trusted loved one or family member to introduce the allergen while you’re not around.

If you choose to go this route, we recommend getting our allergen guide for them. This will ensure that they’re well informed about the signs of an allergic reaction and what to do if a reaction does occur. Plus, they can download it to any device, so they can have it readily available as they introduce the allergen.

Food allergy FAQ

Do allergens need to be introduced in a certain order?

There is no evidence to show that allergens need to be introduced to babies in any specific order.

That being said, we prefer to introduce allergens that are commonly found in other foods (such as milk and eggs) first.

For example, choosing a bread to serve to your baby is much easier when you don’t have to worry about finding one without milk or eggs on the ingredient list.

Does having one allergy increase the chances of developing another one?

Yes.

Babies with one food allergy may be at an increased risk for developing another one (16).

Upon diagnosis of one food allergy, ask your allergist how they recommend introducing other top allergens. They may suggest that this be done supervised in the office, or they might give you the go-ahead to introduce them at home following the regular introduction protocol.

Can I use allergen powders to introduce my baby to allergens?

While you can use an allergen powder to introduce allergens to your baby, these products are absolutely not necessary.

We recommend introducing allergens to your baby through whole foods whenever possible. Not only is it less expensive to use whole foods, but it will also provide your baby with practice eating foods of different flavors and textures.

If you do choose to use a pre-made powder to introduce an allergen to your baby, make sure to use one that only contains one allergen instead of a mixed allergen powder. It’s important to introduce your baby to only one new allergenic food at a time.

Does rubbing a food on my baby’s skin count as an exposure?

No.

It is not recommended to rub food onto your baby’s skin as a method of introducing them to an allergen. Certain foods can be irritating to the skin and may cause a “false positive” rash, which can be mistaken for an allergic reaction. This is especially true for acidic foods, which can cause a non-allergic rash called contact dermatitis.

Plain and simple, the most effective way to introduce an allergen to your baby is to have them ingest it.

Are babies on a cow's milk formula exposed to cow's milk as an allergen?

Yes.

Most baby formula is made from cow’s milk, therefore, if your baby is on a standard cow’s milk-based infant formula, they have technically been exposed to cow’s milk protein as an allergen (40).

An exception to this is for babies who are on a specialized formula such as hypoallergenic, hydrolyzed, or elemental. Although these formulas are often made with cow’s milk, the dairy proteins in these formulas are broken down to the point that the body can no longer recognize the dairy proteins as an allergen (41).

Regardless, even if your baby is on a standard cow’s milk-based formula, we still recommend introducing cow’s milk as an allergen through food and keeping it in your baby’s diet often to maintain their tolerance.

Are allergens passed through breastmilk?

Yes.

Small amounts of food-allergen proteins can be passed along to your baby through your breast milk.

However, it should be noted that there’s conflicting evidence on whether or not exposure to allergens through breastmilk can reduce your baby’s chances of developing an allergy to those foods (42).

In the cases where reduced incidence of food allergy has been observed, it’s usually in combination with early allergy introduction (before age one) through food, which remains the main method for allergy prevention (43).

Bottom line, exposures to allergens through breastmilk are not considered enough to prevent or rule out an allergy (44). Whether your baby is breastfed or formula fed, we always recommend introducing top allergens to your baby through food so that an allergy can be properly ruled out.

What’s the difference between food allergy and food intolerance?

Although they commonly get confused for one another, allergies and intolerances are two very different things.

A food allergy involves an immune response to the protein component of a food. It can result in a very serious, sometimes life-threatening reaction called anaphylaxis (23). Food allergies are what we’re trying to prevent through early introduction of allergenic foods, as discussed in the sections above.

A food intolerance is when a component of a food can’t be properly digested because of a lack of enzymes (27). An example that many people are familiar with is lactose intolerance, where those affected have trouble digesting lactose in dairy products because they don’t produce enough of the enzyme called lactase (27).

Those with lactose intolerance do not have an allergy to cow’s milk protein, and technically can still eat dairy products if they choose. They may even be able to handle certain amounts before symptoms occur. But those with a cow’s milk protein allergy need to avoid all dairy products.

Our 60-Day Baby Led Feeding Meal Plan takes the guesswork out of introducing allergens! It provides 60 days of dietitian-approved recipes with built-in allergen introduction protocols so that there’s no extra planning required by you!

Pin to save for later!

References

- Food Allergy Research & Education. (2025). Facts and Statistics: Key information to help better understand food allergies and anaphylaxis. https://www.foodallergy.org/resources/facts-and-statistics

- Tham, E. H., & Leung, D. Y. M. (2018). How Different Parts of the World Provide New Insights Into Food Allergy. Allergy, asthma & immunology research, 10(4), 290–299. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2018.10.4.290

- Health Canada. (2023, April 18). Common food allergens. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-safety/food-allergies-intolerances/food-allergies.html

- Government of Canada. (2017). Sulphites. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/food-nutrition/reports-publications/food-safety/2017-sulphites-sulfites-eng.pdf

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2024). Food allergies. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/food-allergies

- Kakieu Djossi, S., Khedr, A., Neupane, B., Proskuriakova, E., Jada, K., & Mostafa, J. A. (2022). Food Allergy Prevention: Early Versus Late Introduction of Food Allergens in Children. Cureus, 14(1), e21046. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.21046

- Larson, K., McLaughlin, J., Stonehouse, M., Young, B., & Haglund, K. (2017). Introducing Allergenic Food into Infants’ Diets: Systematic Review. The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 42(2), 72-80.DOI: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000313

- Fiocchi, A., Assa’ad, A., Bahna, S., Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee, & American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (2006). Food allergy and the introduction of solid foods to infants: a consensus document. Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology: official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology, 97(1), 10–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61364-6

- Du Toit, G., Roberts, G., Sayre, P. H., Bahnson, H. T., Radulovic, S., Santos, A. F., Brough, H. A., Phippard, D., Basting, M., Feeney, M., Turcanu, V., Sever, M. L., Gomez Lorenzo, M., Plaut, M., Lack, G., & LEAP Study Team (2015). Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. The New England journal of medicine, 372(9), 803–813. https://doi-org.ezproxy.msvu.ca/10.1056/NEJMoa1414850.

- Fleischer, D. M., Chan, E. S., Venter, C., Spergel, J. M., Abrams, E. M., Stukus, D., Groetch, M., Shaker, M., & Greenhawt, M. (2021). A Consensus Approach to the Primary Prevention of Food Allergy Through Nutrition: Guidance from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology; and the Canadian Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice, 9(1), 22–43.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.002

- Turcanu, V., Brough, H. A., Du Toit, G., Foong, R. X., Marrs, T., Santos, A. F., & Lack, G. (2017). Immune mechanisms of food allergy and its prevention by early intervention. Current opinion in immunology, 48, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2017.08.009

- Jonsson, K., Barman, M., Brekke, H. K., Hesselmar, B., Johansen, S., Sandberg, A. S., & Wold, A. E. (2017). Late introduction of fish and eggs is associated with increased risk of allergy development – results from the FARMFLORA birth cohort. Food & nutrition research, 61(1), 1393306. https://doi.org/10.1080/16546628.2017.1393306

- Mermiri, D. T., Lappa, T., & Papadopoulou, A. L. (2017). Review suggests that the immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory properties of allergenic foods can provoke oral tolerance if introduced early to infants’ diets. Acta paediatrica, 106(5), 721–726. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13778

- Ierodiakonou, D., Garcia-Larsen, V., Logan, A., Groome, A., Cunha, S., Chivinge, J., Robinson, Z., Geoghegan, N., Jarrold, K., Reeves, T., Tagiyeva-Milne, N., Nurmatov, U., Trivella, M., Leonardi-Bee, J., & Boyle, R. J. (2016). Timing of Allergenic Food Introduction to the Infant Diet and Risk of Allergic or Autoimmune Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA, 316(11), 1181–1192. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.12623

- Abrams, E. M., Hildebrand, K., Blair, B., & Chan, E. S. (2019). Timing of introduction of allergenic solids for infants at high risk. Paediatrics & child health, 24(1), 56–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxy195

- Trogen, B., Jacobs, S., & Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. (2022). Early Introduction of Allergenic Foods and the Prevention of Food Allergy. Nutrients, 14(13), 2565. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132565

- Brown S. J. (2016). Atopic eczema. Clinical medicine (London, England), 16(1), 66–69. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.16-1-66

- American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. (2023). Eczema. https://acaai.org/allergies/allergic-conditions/skin-allergy/eczema/

- Greer, F. R., Sicherer, S. H., Burks, A. W., COMMITTEE ON NUTRITION, & SECTION ON ALLERGY AND IMMUNOLOGY (2019). The Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Hydrolyzed Formulas, and Timing of Introduction of Allergenic Complementary Foods. Pediatrics, 143(4), e20190281. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0281

- Gupta, R. S., Walkner, M. M., Greenhawt, M., Lau, C. H., Caruso, D., Wang, X., Pongracic, J. A., & Smith, B. (2016). Food Allergy Sensitization and Presentation in Siblings of Food Allergic Children. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice, 4(5), 956–962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2016.04.009

- Waserman, S., Bégin, P., & Watson, W. (2018). IgE-mediated food allergy. Allergy, asthma, and clinical immunology: official journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 14( 2), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-018-0284-3

- Cox, L. S., Sanchez-Borges, M., & Lockey, R. F. (2017). World Allergy Organization Systemic Allergic Reaction Grading System: Is a Modification Needed?. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice, 5(1), 58–62.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2016.11.009

- Anvari, S., Miller, J., Yeh, C. Y., & Davis, C. M. (2019). IgE-Mediated Food Allergy. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology, 57(2), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-018-8710-3

- Feuille, E., & Nowak-Węgrzyn, A. (2015). Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome, Allergic Proctocolitis, and Enteropathy. Current allergy and asthma reports, 15(8), 50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-015-0546-9

- Kelava, N., Lugović-Mihić, L., Duvancić, T., Romić, R., & Situm, M. (2014). Oral allergy syndrome–the need of a multidisciplinary approach. Acta clinica Croatica, 53(2), 210–219.

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. (2024, January 10). Oral allergy syndrome (OAS). https://www.aaaai.org/tools-for-the-public/conditions-library/allergies/oral-allergy-syndrome-%28oas%29

- Government of Canada. (2023). Food Allergies and Intolerances. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-safety/food-allergies-intolerances.html

- Gargano, D., Appanna, R., Santonicola, A., De Bartolomeis, F., Stellato, C., Cianferoni, A., Casolaro, V., & Iovino, P. (2021). Food Allergy and Intolerance: A Narrative Review on Nutritional Concerns. Nutrients, 13(5), 1638. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051638

- American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. (2018). Anaphylaxis. https://acaai.org/allergies/symptoms/anaphylaxis/

- Abrams, E.M.,Orkin, J., Cummings, C., Blair, B., Chan, E.S., & Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee and Allergy Section (2021). Position Statement: Dietary exposures and allergy prevention in high-risk infants, Paediatrics & Child Health, 26(8), 504–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxab064

- Paulsen, E., Christensen, L.P., & Andersen, K.E. (2012). Tomato contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis, 67: 321-327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0536.2012.02138.x

- American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. (2023). Food Allergy. https://acaai.org/allergies/allergic-conditions/food/

- Halken, S., Muraro, A., de Silva, D., Khaleva, E., Angier, E., Arasi, S., Arshad, H., Bahnson, H. T., Beyer, K., Boyle, R., du Toit, G., Ebisawa, M., Eigenmann, P., Grimshaw, K., Hoest, A., Jones, C., Lack, G., Nadeau, K., O’Mahony, L., Szajewska, H., Venter, C., Verhasselt, V., Wong, G.W.K., Roberts, G. , &European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group (2021). EAACI guideline: Preventing the development of food allergy in infants and young children (2020 update). Pediatric allergy and immunology : official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 32(5), 843–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.13496

- Chan, E. S., Cummings, C., & Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee and Allergy Section (2013). Dietary exposures and allergy prevention in high-risk infants: A joint statement with the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Paediatrics & child health, 18(10), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/18.10.545

- Abrams, E. M., Ben-Shoshan, M., Protudjer, J. L. P., Lavine, E., & Chan, E. S. (2023). Early introduction is not enough: CSACI statement on the importance of ongoing regular ingestion as a means of food allergy prevention. Allergy, asthma, and clinical immunology: official journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 19(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-023-00814-2

- American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (2019). Milk & Dairy. https://acaai.org/allergies/allergic-conditions/food/milk-dairy/

- American College of Asthma, Allergy, & Immunology. (2019). Egg. https://acaai.org/allergies/allergic-conditions/food/egg/

- Nowak-Wegrzyn, A., Bloom, K. A., Sicherer, S. H., Shreffler, W. G., Noone, S., Wanich, N., & Sampson, H. A. (2008). Tolerance to extensively heated milk in children with cow’s milk allergy. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 122(2), 342–347.e3472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.043

- Chomyn, A., Chan, E. S., Yeung, J., Vander Leek, T. K., Williams, B. A., Soller, L., Abrams, E. M., Mak, R., & Wong, T. (2021). Canadian food ladders for dietary advancement in children with IgE-mediated allergy to milk and/or egg. Allergy, asthma, and clinical immunology: official journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 17(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-021-00583-w

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2022). Cow’s Milk Alernatives: Parent FAQs. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/nutrition/Pages/milk-allergy-foods-and-ingredients-to-avoid.aspx

- Isolauri, E., Sütas, Y., Mäkinen-Kiljunen, S., Oja, S. S., Isosomppi, R., & Turjanmaa, K. (1995). Efficacy and safety of hydrolyzed cow milk and amino acid-derived formulas in infants with cow milk allergy. The Journal of pediatrics, 127(4), 550–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70111-7

- Koukou, Z., Papadopoulou, E., Panteris, E., Papadopoulou, S., Skordou, A., Karamaliki, M., & Diamanti, E. (2023). The Effect of Breastfeeding on Food Allergies in Newborns and Infants. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 10(6), 1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061046

- Pitt, T. J., Becker, A. B., Chan-Yeung, M., Chan, E. S., Watson, W. T. A., Chooniedass, R., & Azad, M. B. (2018). Reduced risk of peanut sensitization following exposure through breast-feeding and early peanut introduction. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 141(2), 620–625.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.024

- Gamirova, A., Berbenyuk, A., Levina, D., Peshko, D., Simpson, M. R., Azad, M. B., Järvinen, K. M., Brough, H. A., Genuneit, J., Greenhawt, M., Verhasselt, V., Peroni, D. G., Perkin, M. R., Warner, J. O., Palmer, D. J., Boyle, R. J., & Munblit, D. (2022). Food Proteins in Human Breast Milk and Probability of IgE-Mediated Allergic Reaction in Children During Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice, 10(5), 1312–1324.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2022.01.028

Bianca Gruenewald, RD

Bianca is a Registered Dietitian and works in a client support role at My Little Eater Inc. She's a proud auntie to her three year old niece and four year old nephew!

Bianca Gruenewald, RD

Bianca is a Registered Dietitian and works in a client support role at My Little Eater Inc. She's a proud auntie to her three year old niece and four year old nephew!